|

Inukitut at breakfast, seal for lunch Students tent in tundra at Trent's Arctic bush school

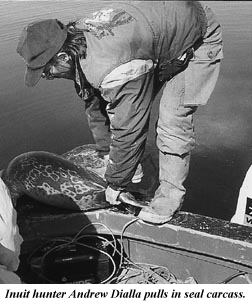

by Martha Tancock "It was a really nice day, really misty. There was a lot of pack ice and the water was really flat and calm. That's when the seals like to come out. We spent most of the time scanning the water for the little dot of a seal head." When they saw one, Dialla nosed the bow towards the quarry, aimed and shot. Then he gunned the boat to reach the seal and gaff it before it sank. Seals have less fat in the summer and sink faster. "After we caught two seals, we stopped at an ice floe for lunch." Dialla butchered a seal and carved pieces of raw liver and ribs for his party to taste. "It was like heavy red meat with a beefy taste and also a fishy taste." Aged walrus meat It was the first of three feasts Buckley and other students partook during Trent's first six-week "bush" school this summer in Pangnirtung. And it was the highlight for Buckley, a fourth-year cultural studies student, one of 25 students enrolled in the experimental program. "I had never seen an animal butchered before let alone eaten raw meat. It was an absolutely new experience." Later, he would eat raw Beluga whale (muktaaq), fermented walrus meat buried for six months that reminded him of "a really sharp blue cheese" ("It makes you warm inside."), and raw, dried caribou and Arctic char. For six weeks, students took daily language classes and attended lectures by native studies professor Peter Kulchyski and cultural studies professor Jonathan Bordo on local history, culture and environment. But the unstructured experiences of life in the north left the most lasting impression. "Those aspects of the trip were the best because I was bombarded by an absolutely new and different life."

Kulchyski selected Pangnirtung for the bush school after visiting the settlement to do his own research on self-government in the north. A self-subsisting hunting and fishing community that was once a whaling station and Hudson's Bay post, it was also the subject of American anthropologist Franz Boa's first profile of Inuit culture at the end of the 19th century. It is near a national wilderness park, has a fishery and arts and craft co-op as well as state-of-the-art teaching facilities and a cultural centre. It also has a nursing station and is "out of range of polar bear country" so it is "very safe," said Kulchyski. Located on a fiord off Cumberland Sound, it is also beautiful. It is surrounded by mountains, glaciers and vast, treeless tundra and is ecologically rich. "I decided to call it a bush school rather than a field school because I wanted to distinguish it from an anthropological approach," said Kulchyski. "I don't know of any other program like this in Canada. Most field schools are run by hard scientists at archeological sites and not in the communities." Bush journals The community connection enriched students' experience. Though they camped on tundra half an hour outside the settlement, they returned daily to the community. They kept "bush" journals, logs of their daily encounters and observations. "It was almost more important than the course" and formed the basis for students' final reports. Students talked to elders, hung out at the local Angmarlik Centre, a cultural and community centre, got to know locals. "I learned not to be shy," says Buckley of the Inuit custom of entering a household without knocking and making yourself at home. "It took a good few weeks to learn how to do that." They were also expected to make some contribution to the community. Some painted, others organized a music festival, a teen dance, a baseball clinic, and created a found-art exhibit at the dump. A few stayed after the course ended to hike in Auyuyttuq National Park and get to know the community better. They completed the course with two credits in cultural and native studies. Kulchyski and Bordo ran the program as two special topics courses with their departments' approval. The university agreed to turn over the tuition fees to pay the program costs, including paying a woman to teach students Inuktitut and giving elders and their interpreters honoraria for speaking to students about their lives and traditional Inuit culture. Students themselves raised about $2,500 in advance by selling T shirts and holding bake sales. The money helped pay for their meals and living expenses. Out of their own pockets, students had to pay tuition fees for two courses and $1,200 in air fare. If the program continues, Kulchyski would probably offer his course again. He also envisions an expanded bush school featuring courses by other faculty in biology, environmental sciences, anthropology, history, Canadian studies. First, however, the academic development committee needs to approve it. Experience a gift Buckley and other students would readily return. He looks upon his experience as a gift. "One thing that is important about receiving a gift in the form of experience is that it requires more time to have a lasting relationship" with the giver. That means revisiting the people of Pangnirtung. In her final report, another student, Peggy Shaughnessy, vows to return to research the myth of sea goddess Sedna. "My heart will always be in Pangnirtung and I will return next summer to see this beautiful land again." She also formed close bonds with her fellow southerners, who reunited to share memories and photos Oct. 31. "The group dynamics that we shared in Pangnirtung will be a feeling that will stay with me throughout my life."

|

Maintained by the Communications Department

Last updated: November 6, 1997

"I'll never think of the Arctic in the abstract way I did before," says Buckley. He plans to return to do master's level research on the history of Inuit arts and crafts.

"I'll never think of the Arctic in the abstract way I did before," says Buckley. He plans to return to do master's level research on the history of Inuit arts and crafts.